I’ll Take the Low Road! Crossing the California Desert and High Sierra

By Peter J. Marsh

A few days into 2015 we saw the pictures of the first ascent of the 3,000-foot Dawn Wall in Yosemite Valley, accomplished by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson. They “free climbed” it — without any artificial aid — which is a stunning achievement in addition to the way the media reacted. This marathon effort succeeded in putting their practically anonymous sport on the top of mainstream news, a breakthrough that cycling made 25 years ago. (For you youngsters, that was when Greg LeMond won the closest ever Tour de France by a mere eight seconds.) Coincidentally, the climbers’ tour de force also took place over 18 days, just like cycling’s grand tours. The two leaders also relied on a dedicated team of helpers.

For me, this brought back 20-year-old memories of my first encounter with Yosemite Valley — the first on foot, the second by bike. My one and only big rock climb happened in Yosemite in 1995 on one of the easiest walls in the valley, the Royal Arches. My modest skill level left me at the bottom of the rope following the two leaders for the entire 1,600 feet. However, I didn’t get an easy ride, as I was appointed the porter, or domestique, for the day, carrying a backpack filled with the spare rope plus water, food, spare clothes and hiking shoes for all three of us!

The next day I took a break to unwind from the high-stress outing. Luckily, there was room in our vehicle to bring my mountain bike along so I could relax in the midst of this incredible geologic wonder while practicing my favorite sport. I rode beside the scenic Merced River, which is fed by the falls and streams that rush down the valley sides, until I reached the noisy highway, then retraced my route to El Capitan, where I stopped to watch the hardcore climbers high above. This was the leading edge of the sport: a wall so big you climbed, ate, and slept up there for many days. Many would-be heroes have had to bail out after a day or two, overwhelmed by the unrelenting nature of the challenge.

This naturally led to me wonder how I ever let anyone talk me into the addictive sport of rock climbing. I loved climbing mountains, not cliffs, and cycling was really where my heart was. If you had told me then that I would one day return to Yosemite by bike after a harrowing 10-day ride across Death Valley, with a quick detour to climb Mount Whitney, I would have laughed out loud. But it only took a couple of years before the seed for that journey was planted.

This naturally led to me wonder how I ever let anyone talk me into the addictive sport of rock climbing. I loved climbing mountains, not cliffs, and cycling was really where my heart was. If you had told me then that I would one day return to Yosemite by bike after a harrowing 10-day ride across Death Valley, with a quick detour to climb Mount Whitney, I would have laughed out loud. But it only took a couple of years before the seed for that journey was planted.

It was 1997 and my 50th birthday was fast approaching. After a lot of hesitation, I gave myself permission to try combining biking and hiking into a “sea-to-summit” climb. At the end of June, I dipped my wheels in the Willamette River in Portland, Ore., cycled east on the familiar Springwater Trail, then joined the traffic on busy Hwy 26 on the climb to Government Camp. I camped near Timberline Lodge at 6,000 feet then hiked to the top of Mount Hood in the morning. The Oregonian found out about this and columnist Jonathon Nicholas wrote a story about it. That gave me a boost for the rest of the summer.

It was the middle of winter before I wondered if I had the energy for another sea-to-summit climb. I made it easier by choosing a volcano in Hawaii, with no hiking needed. I completed the 13,760-foot ride up to the Mauna Kea observatories in nine hours; that left me two weeks to tour around the Big Island and play on the beach.

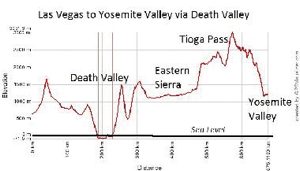

I picked up the pace in 1998 and in the next three years I ticked off all the major peaks of the Northwest Pacific from sea level. The plan was to climb the three 14,000 footers sometime around the millennium. It began with Mount Rainier — accomplished in 48 hours in 1999 after joining a climbing group I found online. Next was Mount Shasta from Red Bluff, solo in four days in the year 2000. That left Mount Whitney, the highest point in the lower 48 states (14,460 feet) with the added attraction of starting in Death Valley (-282 feet), the lowest and hottest point in North America.

Research suggested that the ideal time to start was after August, the hottest month, but before the typical first snowfall in late September. I was checking the new web-based travel sites for inexpensive tickets to Las Vegas when 9–11 happened. A week passed and it was still difficult to think about my trip, all my friends were trying to dissuade me from flying. The other issue was the airlines, which didn’t offer any discounts; they immediately raised their prices, ensuring their planes would be half empty.

When I finally reached the luggage carousel in Las Vegas, I was the only passenger in sight! I emerged into the afternoon sun to find it was so hot that I could barely concentrate on assembling my folding Bike Friday on the sidewalk. Eventually I rode slowly into the city center and passed the exotic sights of the Strip, then headed out into the desert at sunset. Late at night, I slept well in the scrubland opposite a brightly-lit compound. At first light, I was up and identified this as a penitentiary, then rode off at a good pace until noon.

Who would want to start a climb at 280 feet below sea level?

As the temperature kept rising, I reached my limit when I rolled into Death Valley Junction, where a stagecoach stop turned into a rustic resort with a famous small theater. I was able to find some salt at the counter in the restaurant because I realized I needed to spike my sports drink mix. I drank copious amounts and sat around for several hours. I finally left after the temperature had dropped to a mere 90 degrees; I still had to climb up to the top of the canyon wall before I began the epic descent into Death Valley.

I will never forget the bizarre sensation I felt: the lower I went, the hotter the headwind became. At the bottom, it felt like I was standing in front of a blast furnace! I finally reached the aptly-named Furnace Creek, 174 miles from Las Vegas, around 8 p.m. Luckily, the store was still open, so I lurked inside in the air conditioning until 9 p.m., when it closed. On the porch, the thermometer read exactly 100 degrees. I took a photo of it, then found my way to the golf course and laid down under a tree, still sweating. It stayed that hot until well after midnight. Looking back, I should have continued riding to Badwater by moonlight, but I needed to rest.

At first light I looked around and found a place to stash my panniers. I set off at a good pace down to Badwater, 18 miles and 70 feet lower. I didn’t note the time I arrived at the official low point, but couldn’t stay long on the white salt flat because I could already feel the heat building. I had a tough time on the return trip after I finished my third bottle of water.

At 11 a.m., the buffet at the resort’s restaurant opened. I drank a couple of quarts of juice then attacked the salad bar with a vengeance. The next step was obvious: buy a day pass and lay in the shade or by the pool — with my hat on! The temperature peaked at 118 and I didn’t get dressed until it dropped toward 100 when I reluctantly loaded the bike and took off into the sunset. The low and high points are only 85 miles apart on the map; by road it is 135 miles with two 5,000-foot passes to overcome. For the next four days I rode from sunrise to noon on a dull diet of snacks from the resorts and gas stations, washed down with lukewarm water, salt and lemonade powder. In the afternoon, I retreated into any available shade until evening. The one day I remember clearly was when I encountered a movie crew filming a car commercial on the Panamint Flat. They adopted me for the afternoon and kept me cool and well hydrated.

When I reached Lone Pine (3,727 feet) in the Owens Valley, I was really dehydrated and resorted to a giant milk shake at the drive-in, which did the trick, and checked in with the forestry office to get a permit to climb Mount Whitney. The first step was the ride up to Whitney Portal, another 5,000 feet. (I was aware that some endurance athletes with nothing better to do, jog this entire 135-mile route in the Badwater Race — one of the dumber ironman events — and a few carry on up the mountain to prove their superiority.) Trust me, it was no easy ride as a cycle tourist!

At the portal I paid my fee, picked up my bear-proof food container and hiked three miles to the camp in a meadow at 10,000 feet. It took over an hour, wearing my lightweight daypack with both hands full of stuff bags holding my camping gear. The next day I summoned my remaining energy and began hiking up the trail. When I slumped down at the top of the arduous switchback section, a cheerful young group of hikers arrived. I told them what I was doing and they encouraged me as we followed the winding route to the flat, wide summit.

I was on my own coming down, which is always hard on the legs. Back at the camp, I ate a little then fell asleep, only to be awakened in the early morning by strong winds and snow flurries. I packed hurriedly and hustled back to my bike, still U-locked to a solid fence. After a fast but chilly downhill, I was soon back in the valley and warming up. I was hoping to find a bus to Los Angeles, but that service had ended long ago, so I continued north following Hwy 395 through the Owens Valley with dramatic views of the Sierra scarp to the west.

The next day I struggled over 8,000-foot Deadman Pass, where I was caught by an Austrian couple touring the U.S. They made a witty comment about me “looking like a dead man,” then paced me over the summit and down into a campground at scenic June Lake, where they cooked and shared with me a real dinner. On my tenth day we rode on to Lee Vining (6,780 feet) above Mono Lake. I was hoping this time there might still be bus service into Yosemite National Park, but it too had ended for the winter.

For the second time I was running on empty and desperately tried to hitch a ride over 9,950-foot Tioga Pass. That was a total waste of time and made me feel pathetic, so I reluctantly mounted up and started climbing the busy cross-Sierra route. Now I was off the edge of my tourist map and riding into the unknown on yet another never-ending ascent. Two hours later, to add insult to injury, I had to pay a $10 entry fee when I reached the park gate at 9,950 feet. The ranger handed me a park map, but I didn’t pay it much attention — I just pictured the route as downhill all the way to the Sacramento Valley.

The road went around lovely Tenaya Lake, past outcrops of granite that were covered in climbing routes. But there were no climbers, as it was fall at this altitude, and I needed to lose some elevation to warm up by nightfall. The sun was setting when I was surprised to encounter the sign pointing to Yosemite Valley. This gave a moment’s relief, but I wasn’t about to take a detour. I pushed on westward into the night and to another roadside camp.

After 11 days of non-stop effort and more than 600 miles and seven passes totaling in excess of 25,000 feet (plus the day on Mount Whitney), the journey ended in the Sacramento Valley at the Greyhound bus station in Modesto. All I had to do was find a cardboard box big enough to hold the Bike Friday, which I found at the back of a furniture store a couple of blocks away. I stayed awake on the long ride back to Portland, Ore., where I had a comfortable view of the awful stretch of I-5 I had ridden the previous summer from Red Bluff to Dunsmuir on my previous Mount Shasta sea-to-summit epic.

Sometime later, I reviewed the journey and added Mount Whitney to the list on my website. It was only then I realized I could include another sea-to-summit: Royal Arches from Death Valley, 282 feet below sea level. Yes, it’s a bit contrived, but rock climbing is full of esoteric classifications of difficulty, so I’m making this my minor contribution to the Yosemite record book.

Side bar: Technically, Death Valley is not a “valley,” which is formed by the action of a river, but a “graben,” formed by the action of block faulting in the earth’s crust.

Peter J. Marsh is an outdoor and nautical writer. He was the editor of Oregon Cycling from 1988-1991. He wrote Rubber to the Road — a guidebook to bike rides around Portland (rubbertotheroad.com). He lives in Astoria, Ore., when not traveling the world on his bike. More of his writing can be found at sea-to-summit.net